Addiction brings people to their knees. From damaging brain cells to causing long-term health problems such as cirrhosis of the liver and heart disease, addiction ravages every part of the mind and body. Current addiction treatment, such as cognitive-behavioral therapies and Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT), is essential for those with substance use disorders (SUD). Unfortunately, even with these approaches, more than 67,000 Americans succumbed to a drug-involved overdose in 2018, including illicit drugs and prescription opioids, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Additionally, relapse rates still hover around 50 percent. With these statistics, it is time to take a hard look at using other clinical approaches during addiction recovery, and exercise should be at the top of the list.

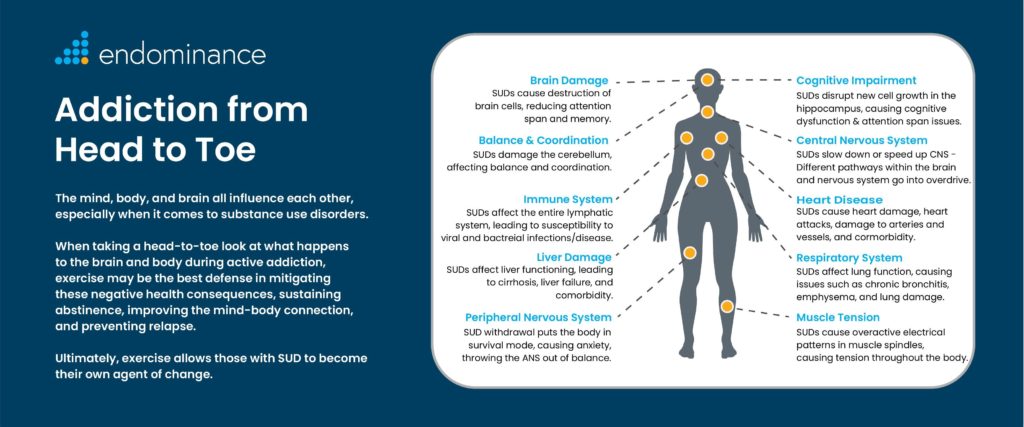

This article will be the first in a series examining the latest research and insight from thought leaders in the healthcare industry on how exercise may be our best defense in sustaining abstinence and preventing relapse for those in addiction recovery. In this paper, we take a head-to-toe look at what happens to the brain and body during active addiction and review the current care practices used during treatment. We then explore how exercise needs to be implemented as a clinical tool to mitigate the negative health consequences of SUDs, improve the mind-body connection, and allow those who are battling an addiction to become their own agent of change.

Addiction, the Brain, and the Economy

When examining addiction from a neurological standpoint, it is clear that drugs and alcohol affect the brain and interfere with the way neurons send and process signals. Substances such as heroin activate neurons because their chemical structure imitates the natural neurotransmitters in the body. However, these neurons are not stimulated in the same way as a natural neurotransmitter, leading to abnormal messages sent throughout the brain (National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIDA). Drugs and alcohol also affect the brain’s reward circuit and cause nerve cells to release too much dopamine into the nucleus accumbens. However, after repeated substance use, neurons begin making less dopamine, receptors are depleted, and the high is reduced. Now, the brain sends out an even stronger desire for the substance, leading to addiction. Dopamine not only contributes to the experience of pleasure, but it also plays a role in learning and memory – two critical elements in the transition from liking something to becoming addicted to it (Harvard Health).

According to John J. Ratey MD, an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and author of the book Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain, “while dopamine in the reward center causes the initial interest or behavior in the drug and provides the motivation to get it, what makes addiction such a stubborn problem is the structural changes it causes in the brain (Ratey, 2008).” These structural and functional changes affect several aspects of the brain, including multiple circuits, receptors, neurons, and the cerebellum. These areas control reward-processing, learning, balance and coordination, executive functions, impulse control, stress, and several systems throughout the body. For example, addiction wires in a memory that becomes reflexive, and once the reward has the brain’s attention, the brain remembers the sensation in vivid detail, and a habit is formed. “With those suffering from a SUD, it’s not so much that they make bad choices; they fail to inhibit behavior that has become reflexive (Ratey, 2008).” While current addiction treatments are necessary and can be effective in those with a SUD, significant national problems still remain. According to Science Advances, in the U.S. alone, there are more than:

-

16 million heavy alcohol drinkers

-

50 million illicit drug users (4.4 million had a marijuana use disorder)

-

10 million people who misuse opioids (Xu, B. & LaBar, K., 2019)

Addiction also costs our nation over $700 billion annually in crime, lost work productivity, and healthcare. Moreover, even if a person wants treatment, many insurance plans do not cover care costs, which averages $6,000 for a 30-day inpatient rehab stay. With all of these healthcare and societal costs still looming in the U.S., it is time to take a hard look at other clinical interventions in treating addiction.

Exercise is Medicine

Historically, exercise has been looked at as a “complementary therapy” in addiction treatment. Substantial research, with more continuing to emerge, shows physical activity, in different intensities and forms, can be a clinical game-changer during SUD recovery. A review article in Frontiers in Psychiatry cites how animal research has shown evidence of neurobiological mechanisms induced by physical exercise to support its potential use as a therapeutic strategy to treat addiction (Costa, K.G. et al., 2019). Examples of how exercise improved the brain during the study include:

-

Normalizing dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmissions.

-

Promoting epigenetic interactions mediated by BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor). BDNF promotes brain cell growth and cognitive performance.

-

Modifying dopaminergic signaling in the basal ganglia.

As we see from this study (and many more throughout this paper) aerobic exercise improves brain cell function and resiliency. Moreover, physical movement, in many forms, improves the cerebellum’s cognitive and motor functioning and helps re-balance the nervous system which affects multiple organs throughout the body. For those in recovery, exercise truly engages the mind and helps it move in a direction other than towards the drug – it wires in an alternative reflexive behavior. Participating in physical activity helps those battling addiction begin to realize that they are in control – they are the agent of change. They can find pleasure without the drug, and this is vital in resisting the urge to use and preventing relapse.

Addiction: Head to Toe

Below, we take an intricate head to toe look at what happens to the brain and body during active addiction and explore the connections between physical activity and the brain and how an exercise-based treatment and intervention plan can help restore the mind and body during recovery.

Brain Damage

Those with a substance use disorder often suffer from the destruction of brain cells, reducing attention span and memory. For example, methamphetamine addiction can result in protein changes in the brain that lead to subsequent cell death and brain inflammation (Science Daily, 2007). According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), current addiction care protocols include a variety of cognitive-behavioral modalities and Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT). Both approaches, used together, can restore a degree of normalcy to brain function and behavior. For instance, common MAT treatments in those with an opioid use disorder (OUD) include:

-

Methadone (Methadose) – used to treat opioid addiction.

-

Buprenorphine (Subutex) – used to treat opioid dependence.

While many addiction professionals feel that MAT is critical during treatment, cost and access issues may surround some of these medications. For example, methadone is only available through approved intensive outpatient programs (IOP) or by a doctor. If someone lacks the money or insurance to cover costs, they will not have access to this medication. Buprenorphine is scarce in rural America. Millions of rural Americans live in counties without a single clinician licensed to prescribe the drug (Sable-Smith, B., 2019). So what happens when MAT or cognitive therapies are not available? Exercise is a free and effective clinical tool that can reduce pain, curb cravings, and aid in the rebuilding of cells in the brain.

Physical activity helps regulate impulsivity and drug cravings by activating the prefrontal cortex regions of the brain responsible for executive function. Acute effects of aerobic exercise in SUD patients have been shown to include increases in prefrontal cortex oxygenation associated with greater inhibitory control and improved memory, attention, and speed processing in polysubstance users (Costa, K.G. et al., 2019). This activation in the brain also helps those in recovery replace their cravings and old behaviors with new coping strategies and healthy habits. Exercise also prompts the brain cells to send out growth factors like BDNF – helping to rebuild new connections between cells. During physical activity, the body releases FNDC5 (a protein) into the bloodstream, according to a study from Harvard Medical School and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Saltus, R., 2013). This protein boosts the expression of BDNF in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. This mechanism of action helps control brain deterioration by protecting brain cells and stimulating the growth of new nerves and nerve connection points.

Working out is also known to reduce pain by increasing natural receptors such as endorphins and endocannabinoids – or cannabis-like substances that travel through the bloodstream and activate receptors in the spinal cord, blocking pain signals from getting to the brain. A study, led by Dr. Philip Sparling of Georgia Tech University, asked young men to either run, cycle, or sit. If they ran or cycled, participants built up to a 70-80 percent heart rate, sustained it for 45 minutes, and then cooled down. The researchers documented a dramatic endocannabinoid increase in the participants who ran and cycled. In addition to current addiction care modalities, a targeted exercise-based treatment plan can help reduce pain and curb cravings and restore brain function and behavior in patients during recovery.

Cognitive Impairment

It is well-known that drugs like marijuana have an impact on attention span as well as short and long-term memory. However, cognitive impairment can result when substances of any kind are misused or abused, including:

-

Excessive alcohol consumption can damage the cerebellum, increasing the risk of falling, cognitive dysfunction, balance and coordination issues, and dementia (Baron, M., 2018).

-

Stimulant addiction results in learning and memory deficits (Kutlu, M.G. & Gould T.J., 2016).

-

Chronic exposure to opiates reduces the birth of new neurons in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, affecting learning and memory (Rapeli, P. et al., 2006).

During inpatient treatment, addiction professionals may utilize different cognitive training programs to help patients build new neural pathways, and stimulant medication may also be used in some instances as cognitive enhancers (Perry, C.J. & Lawrence, A.J., 2016). Researchers now believe that any form of physical movement, including mind-body exercises like Tai Chi and yoga, may also help restore the cerebellum’s cognitive and motor functioning. A recent study suggests in addition to motor functioning, the brain’s cerebellum is also responsible for controlling cognitive functions, such as learning and attention. With this new information, researchers believe that this area could also regulate reward-processing and addiction (Carta, I. et al., 2019).

An exciting new study protocol is currently examining how exercise intervention consisting of circuit training, functional movement, and primitive reflex training can help reduce the recovery time of cognitive functioning during the early phase of addiction treatment. The study cites that one of the more significant problems in exercise research [concerning SUD treatment] is the inadequate description of the protocol, such as dose, intensity, and how exercises are implemented (Andreassen, O. et al., 2019). This study looks to address and correct this issue by using exercise as an actual form of clinical treatment and intervention for those with a SUD.

We know that drugs, like opiates, disrupt new cell growth (neurogenesis) in the hippocampus, causing memory and attention span issues. Fortunately, our bodies produce a human growth hormone (HGH), a chemical naturally secreted by the brain’s pituitary gland that stimulates cell growth and reproduction, keeping neuroplasticity and neurogenesis moving smoothly until we age and levels drop. Exercise is a natural way to boost HGH to encourage new cell growth in our brains during addiction recovery. Phil Campbell, an elite personal trainer, started experimenting with high-intensity interval training (HIIT) programs. During his workouts, he noticed he was getting much higher gains with sprints, which takes a person from an aerobic phase into the anaerobic zone – or HIIT. However, what surprised Campbell was the rapid increase of naturally occurring HGH. He found that not only does HGH increase muscle growth and retention, but it also presents numerous cognitive and neuroprotective effects (Bowyer, J., 2017).

Balance and Coordination

Chronic substance misuse and abuse can damage the cerebellum, affecting motor functions such as walking, speech, and balance and coordination, also known as ataxia. Alcohol plays a more significant role in damaging the cerebellum, especially when consumed excessively over a long period.

During addiction treatment, those suffering from balance and coordination issues will slowly begin to regain some motor skills over time – but only if they abstain from substances. However, depending upon the duration and amount of alcohol or drugs consumed, some people may suffer from balance and coordination issues for years after recovery. Current treatments for ataxia include medications such as acetazolamide as well as having patients avoid triggers such as stress and caffeine. High doses of vitamin E is also known to help stop disease progression and lead to some neurological improvement (Science Daily, 2015). Despite these treatments, there is no cure for these motor function issues, especially in those with chronic ataxia.

Since older populations tend to be the most at-risk for alcohol-related ataxia, researchers are now looking at ways to help those with coordination and balance issues through yoga. Growing research is finding that yoga shows tangible physical improvements such as increased flexibility, better balance, and increased strength, especially in those with neurological issues. One study conducted a review to determine the impact of yoga-based exercise on balance and mobility in people aged 60 and older. The results showed that yoga interventions resulted in improvements in balance and physical mobility (Youkhana, S. et al., 2015).

The Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

Prolonged substance abuse affects the nervous system, which consists of the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system (the nerves outside the brain and spinal cord). Depressants, such as alcohol, slow down the central nervous system (CNS), affecting the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which leads to feelings such as drowsiness, relaxation, and decreased inhibition. Stimulants such as cocaine excite the CNS by stimulating the release of dopamine; however, it also blocks the release of GABA, which prevents the reabsorption of dopamine. This action causes alertness, euphoria, and impaired decision-making. When someone stops using drugs or alcohol, different pathways within the brain, as well as the entire nervous system, go into overdrive. This period of acute withdrawal from substances produces a variety of adverse effects such as nausea, irritability, insomnia, and headaches, depending on the dosage and the length of misuse. However, effects may last weeks or months and include symptoms such as:

-

nervousness and twitchy behavior

-

agitation

-

insomnia

-

tremors and shakiness

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) and its subdivision the autonomic nervous system, which includes the sympathetic and parasympathetic regions, are also affected by chronic substance abuse. Stephen Porges, professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, is best known for developing the polyvagal theory (Porges, 2011) which helps addiction health professionals understand the interplay between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomous nervous system when dealing with trauma, pain, and substance use disorders. This theory also includes the vagus nerve that exits the brainstem and travels through almost every part of the body. The polyvagal theory consists of three branches of the autonomous nervous system and their corresponding responses, including:

-

Immobilization – parasympathetic system

-

Fight or flight system – sympathetic system

-

Social engagement system – the ventral vagal

From Porges’ work, it is now known that the ventral vagal, or social engagement system, is in charge during non-threatening situations. It functions as a kind of brake that slows down our heart and other organs, allowing our system to calm down. Withdrawal from substances causes major disruptions throughout all three systems and leaves most individuals in the “fight or flight” mode, resulting in feelings of agitation, aggression, and stress. Current treatments for withdrawal symptoms include medications such as MAT, benzodiazepines, or beta-blockers to decrease agitation/anxiety and alleviate insomnia. These treatments are beneficial in the short-term, but some of these medications are not recommended for long-term use.

During recovery, the autonomous nervous system needs to be toned down and re-balanced. Exercise activates the system in a way that releases tension. It increases serotonin and norepinephrine, which not only promotes relaxation, but also calms the amygdala – the area of the brain that contributes to emotional processing and sends distress signals to the hypothalamus. Physical activity also increases the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA as well as BDNF, which is essential for feeling more relaxed and less “twitchy,” but also for cementing alternative responses and habits (Ratey, 2008). Doing yoga, Tai Chi, or any other mind-body activity can also help restore the proper balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, creating a feeling of calm.

Anxiety and Depression

For those struggling with depression and anxiety, drugs and alcohol offer a solution in treating the symptoms of these mental health disorders. Over time, substance use exacerbates symptoms of depression and anxiety, creating a SUD and a vicious cycle of use. The biology of stress and anxiety ties in with addiction in that withdrawal puts the body in survival mode. If a patient suddenly quits drinking, dopamine shuts off, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [VP5] gets thrown out of balance (Ratey, 2008). This axis consists of the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. During withdrawal, the body is in fight or flight mode, even without an actual threat. The hypothalamus releases a corticotropin-releasing hormone that travels to the pituitary gland, triggering the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone. This hormone travels to the adrenal glands, prompting them to release cortisol. The body stays revved up and on high alert. When the threat passes, cortisol levels fall. The parasympathetic nervous system, the “brake,” then dampen the stress response (Harvard Health, 2011).

Current options for treating co-occurring disorders include medications like beta-blockers and anti-depressants to relieve anxiety, as well as inpatient treatment and counseling. While these treatments are effective, anti-depressants can become too costly, especially without insurance. In 2018, nearly 100,000 people in the U.S. needed drug addiction treatment but never receive it because their insurance did not cover treatment costs according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). A study out of China found that physical exercise increases the abstinence rate in subjects with SUD and eases withdrawal symptoms, anxiety, and depression symptoms. Additionally, mind-body exercises, such as Qigong and yoga, have similar treatment effects as to aerobic exercise (Wang, D. et al., 2014). Exercise can significantly improve feelings of anxiety and depression by:

-

Reducing muscle tension – exercise serves as a circuit breaker just like beta-blockers, interrupting the negative feedback loop from the body to the brain that heightens anxiety.

-

Teaching a different outcome – anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system (increasing heart rate and breathing). However, those same symptoms are inherent to aerobic exercise, which is a good thing. If individuals associate the physical symptoms of anxiety with something positive, something the person initiated and can control, the fear memory fades in contrast to the healthy one taking shape (Ratey, 2008).

The Immune System

Long-term struggles with alcohol or drugs can lead to considerable damage to the immune system. The lymphatic system plays an important role in the immune system. It houses an extensive network of vessels that allow for the movement of lymph, a fluid, to circulate throughout the system. When someone continually injects, smokes, or snorts a drug, this leads to significant scarring of the lymphatic system – facilitating the blockage of lymphatic vessels and nodes. This chronic use of substances, including alcohol, eventually leads to a reduction in antibody production and a suppressed immune system. Once the immune system is suppressed, susceptibility to infections and diseases increases dramatically. For example, recent evidence suggests that cocaine use leads to critical changes in the immune system, with significant effects on T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells and influencing peripheral levels of cytokines (Zaparte, A., et al., 2019).

During addiction recovery, it is highly recommended that patients eat healthily, reduce stress, and exercise to boost their immune system to ward off potential infections. We know that chronic stress suppresses the immune system and keeps individuals from sticking with their usual healthy routines (such as eating a balanced diet or getting enough sleep). But how does exercise directly impact the immune system? A compelling review study (Nieman, D.C. & Wentz, L.M., 2019) out of the Journal of Sport and Health Science summarized research discoveries within 4 areas of exercise immunology:

-

The acute and chronic effects of exercise on the immune system.

-

The clinical benefits of the exercise–immune relationship.

-

The effect of exercise on immunosenescence (deterioration of the immune system brought on by age).

-

The nutritional influences on the immune response to exercise.

The study concluded that moderate to vigorous exercise, done in sessions of less than an hour, has a dramatic impact on the immune system, decreases the risk of illness, and that exercise overall has an anti-inflammatory effect on the body. This study is just one of many that demonstrate how working out regularly can have a direct impact on the body’s line of defense.

The Respiratory System

Chronic drug use can lead to a variety of respiratory problems which often presents in many different ways. Marijuana smoke can cause acute chest illnesses (bronchitis) and other toxic, lung-related infections and injury. Smoking crack cocaine can cause lung damage and severe respiratory problems. Heroin use can result in certain lung complications including tuberculosis and pneumonia due to the drug’s depressing effects on respiration. Opioids also cause breathing to slow, making asthma symptoms worse. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is often recommended during addiction recovery for those with chronic lung disease or another condition that makes it hard to breathe or limit activities. PR often includes exercise, medications, and breathing exercises designed to increase oxygen levels and help airways to stay open longer.

However, PR may not always be available to patients due to a lack of resources and health insurance. If patients do not have access to this type of program, they can take steps on their own to help improve respiratory function, including stopping smoking and exercising regularly. Dr. Aaron Waxman, director of the Pulmonary Vascular Disease Program at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital explains, “about a year after you quit, the inflammation that causes tissue damage will abate, and then over the next few years the decline in lung function will return to its normal pattern (Harvard Health, 2018).” According to the American Lung Association, when someone is active, the heart and lungs work harder to supply the additional oxygen the muscles demand. As a person’s physical fitness improves, the body becomes more efficient at getting oxygen into the bloodstream and transporting it to the working muscles. Any form of moderate activity can help improve the respiratory system and muscle-strengthening activities like weight-lifting or Pilates build core strength, improving posture as well as breathing muscles.

Muscle Tension

During addiction withdrawal and recovery, the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomous nervous system are out of balance, often causing feelings of anxiety and stress. Sometimes, this form of anxiety can physically manifest into overactive electrical patterns in muscle spindles (somatic anxiety) and cause muscle tension throughout the body. This physical tension can lead to impulsivity, aggression, stress, and relapse.

Current options for treating withdrawal symptoms such as tension and anxiety include medications like beta-blockers and anti-depressants as well as inpatient treatment and counseling. These treatments are necessary for many patients and can help in the short term. However, with relapse rates still hovering at 50 percent, the long-term outlook in treating co-occurring disorders requires treating the whole person and this should include clinical interventions such as exercise. Working out reduces levels of the body’s stress hormones, such as adrenaline and cortisol, and interrupts the anxiety loop from the body to the brain (the HPA axis). While physical exercise can help relieve tension, stress-reducing relaxation exercises, such as yoga and meditation, can help individuals learn how to control bodily sensations and remain calm in the face of anxiety.

Liver Problems

In terms of addiction, the most common form of damage done to the liver occurs from alcoholic liver disease. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the number of deaths from alcoholic liver disease in the United States in 2017 was 22,246 (CDC). Drugs, like heroin, can also cause significant damage to the liver, and the cost is worse when drugs are combined with other substances. Current treatments for comorbid disorders include psychosocial interventions and medications (Addolorato, G. et al., 2016). However, long-term use of these medications may result in poor outcomes, and those without insurance will find it difficult to afford and attain the quality care they need to treat comorbid disorders.

Exercise can be used to help decrease stress on the liver, increase energy levels, and prevent obesity – a risk factor for liver disease. Building lean muscle mass through weight training can delay severe muscle wasting that becomes apparent during advanced stages of liver disease. A University of Missouri School of Medicine study also found that aerobic exercise promotes healthier mitochondria and a higher-working metabolism, which work together to bolster the liver. “We know from previous research that chronic drinking causes modifications to protein structures within the liver, resulting in irreversible damage. In our current study we wanted to see whether increased levels of aerobic fitness could prevent alcohol-related liver damage,” states Jamal Ibdah, lead author of the study (Science Daily, 2019). The research team used rats bred for high activity to test if increased metabolism protected the liver against fatty deposits and inflammation. As the researchers expected, the chronic alcohol group of rats had more fatty deposits in their livers (a sign of liver damage). However, excessive alcohol ingestion didn’t lead to any liver inflammation thanks to the rats’ high metabolisms and mitochondrion. Aerobic exercise seemed to protect against the metabolic dysfunction that causes irreversible liver damage.

Heart Disease

Substance misuse and abuse can cause adverse cardiovascular effects, ranging from abnormal heart rate to heart attacks. However, once a person stops using drugs or alcohol, it can reduce their chances of heart damage. For example, quitting methamphetamine use can reverse damage to the heart and improve heart function in those with a SUD when combined with appropriate medical treatment (Napoli, N., 2017). Current addiction recovery treatment advises exercise as a complementary tool in gaining strength and improving heart function; however, physical activity needs to be looked at as more than an “alternative” therapy during recovery. Exercise controls the emotional and physical feelings of stress and works at the cellular level. “During physical activity, neurons are challenged – just like muscles, making them more resilient. This is how exercise forces the body and mind to adapt (Ratey, 2008).” Reducing stress during addiction recovery is crucial to improving cardiovascular function, and utilizing exercise, in any form, can be the difference between life and death.

A Call to Action

The mind, body, and brain are highly interconnected, especially when it comes to substance use disorders. Growing research continues to reveal how exercise may be our best defense in sustaining abstinence, improving overall health, and preventing relapse for those in addiction recovery. When taking a head-to-toe look at what happens to the brain and body during active addiction, we see that physical activity can be vital in mitigating negative health consequences and improving the mind-body connection. Ultimately, exercise allows those in addiction recovery to improve their quality of life and gain the confidence needed to know they have control – they can become an agent of change. Now that we know physical activity has the ability to treat those with a SUD on a neurological and systemic level, we need to expand the current addiction treatment protocols to include exercise as a clinical standard of care. When we know better, we must do better.

Follow us as we continue our Addiction: Head to Toe series examining the latest research and insight from leading healthcare professionals on how exercise may be our best defense in sustaining abstinence and preventing relapse for those in addiction recovery.

Disclaimer: The exercise and medical information in this paper should not be followed without first consulting a medical health professional. This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to prevent, cure, or treat any diseases.

References:

Addolorato, G. et al. (2013). Management of alcohol dependence in patients with liver disease. CNS Drugs. 27(4): 287–299. doi.org/10.1007/s40263-013-0043-4.

Andreassen, O. et al. (2019). The effect of high-intensity interval/circuit training on cognitive functioning and quality of life during recovery from substance abuse disorder. A study protocol. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02564

Baron, M. (2018, October 24). The Impact of Addiction and Addictive Substances on Memory. Psychology Today. Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-verge/201810/the-impact-addiction-and-addictive-substances-memory.

Bowyer, J. (2017, June 5) Ultra-High Performance Training. Forbes. Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jerrybowyer/2017/06/05/ultra-high-performance-training/#14a8bf032bab.

Carter, I. et al. (2019). Cerebellar modulation of the reward circuitry and social behavior. Science Magazine. 18(363). doi: 10.1126/science.aav0581

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol Use. (2017). Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/alcohol.htm.

Costa, K.G. et al. (2019). Rewiring the addicted brain through a psychobiological model of physical exercise. Frontiers in Psychiatry. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00600.

Harvard Health Publishing. Breathing Life into Your Lungs. (April, 2018). Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/lung-health-and-disease/breathing-life-into-your-lungs.

Harvard Health Publishing. How Addiction Hijacks the Brain. (July, 2011). Retrieved April 1, 2020, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/how-addiction-hijacks-the-brain.

Harvard Health Publishing. Understanding the Stress Response. (March, 2011). Retrieved April 30, 2020 from https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response.

Kutlu, M.G. & Gould T.J. (2016). Effects of drugs of abuse on hippocampal plasticity and hippocampus-dependent learning and memory: contributions to development and maintenance of addiction. Learning and Memory. 23(10): 515–533. doi: 10.1101/lm.042192.116.

Napoli, N. (2017, May 30). Stopping Drug Abuse Can Reverse Related Heart Damage. American College of Cardiology. Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.acc.org/about-acc/press-releases/2017/05/30/09/59/stopping-drug-abuse-can-reverse-related-heart-damage

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drugs and the Brain. (July, 2018). Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/drugs-brain.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose Death Rates. (March, 2020). Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. What Are the Treatments for Heroin Use Disorder? (June, 2018). Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/heroin/what-are-treatments-heroin-use-disorder.

Nieman, D.C. & Wentz, L.M. (2019). The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 8(3): 201-217. doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2018.09.009

Perry, C.J. & Lawrence, A.J. (2016). Addiction, cognitive decline, and therapy: seeking ways to escape a vicious cycle. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 16(1): 205-218. doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12325.

Porges, S. (2011). Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: Norton.

Rapeli, P. et al. (2006). Cognitive function during early abstinence from opioid dependence: a comparison to age, gender, and verbal intelligence matched controls. BMC Psychiatry. 6(9). doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-6-9.

Ratey, J. J. (2008). Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. Little, Brown and Company.

Sable-Smith, B. (2019, December 30). In Rural Areas Without Pain or Addiction Specialists, Family Doctors Fill in The Gaps. NPR. Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/12/30/786916670/in-rural-areas-without-pain-or-addiction-specialists-family-doctors-fill-in-the-

Saltus, R. (2013, October 10). Exercising the Mind. Harvard Medical School. Retrieved May 19, 2020 from https://hms.harvard.edu/news/exercising-mind

Loyola University Health System. (2015, March 23). Cerebellar ataxia can’t be cured, but some cases can be treated. ScienceDaily. Retrieved May 1, 2020 from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/03/150323150536.htm

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHDetailedTabs2018R2/NSDUHDetTabsSect7pe2018.htm#tab7-65a.

University of Missouri-Columbia. (2016, February 16). Aerobic fitness may protect the liver against chronic alcohol use: Higher metabolism from aerobic activity could prevent liver inflammation. ScienceDaily. Retrieved May 19, 2020 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/02/160216123453.htm.

University of Florida. (2007, November 30). Club Drugs Inflict Damage Similar to Traumatic Brain Injury. Science Daily. Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/11/071129121127.htm.

Wang, D. et al. (2014). Impact of physical exercise on substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 9(10). Article e110728.

Xu, B. & LaBar, K. (2019). Advances in understanding addiction treatment and recovery. Science Advances. 5(10).

Youkhana, S. et al. (2016). Yoga-based exercise improves balance and mobility in people aged 60 and over: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and Ageing. 45(1) 21-29. doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv175.

Zaparte, A., et al. (2019). Cocaine use disorder is associated with changes in Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokines and lymphocytes subsets. Frontiers in Immunology. 10(243-245). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02435.