In an American Psychological Association special report, Roger Weissberg, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and chief knowledge officer of the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) states, “If you look at the prevalence of kids who have school adjustment difficulties, behavioral issues, and mental health problems, it was too high before the pandemic — and it’s going to be higher now.”

So how can educators effectively help students navigate these behavioral difficulties and classroom challenges? Current educational models encourage teachers to use control and compliance-based measures in classroom management. Unfortunately, research shows these methods just aren’t working. They do not create sustainable changes in student behavior. It’s time to understand students’ behaviors through the lens of their physiological states.

Below, we speak with Dr. Lori Desautels on how specific brain-aligned preventive methods (based on educational neuroscience) combined with the Polyvagal Theory have shifted how educators now understand and address student behavior. We also discuss how “state regulation” helps students and teachers access and integrate the cognitive and mental tasks they need to navigate both classroom and real-world challenges successfully.

The Truth Behind Traditional Discipline in Schools

Detentions, suspensions, being called out in front of the class, and other forms of school punishment have dominated educational systems for decades. Yet, if we had to grade these forms of classroom management today – they would receive a resounding “F.” Thought leaders in education now see that traditional punishment only escalates power struggles and conflict cycles, generating an increased stress response in the student brain and body. So how do we address these issues and use conflict as an opportunity to problem-solve? Endominance spoke with Dr. Lori Desautels on specific brain-aligned preventive methods used as therapeutic techniques when dealing with student behavioral issues. Desautels, Assistant Professor in the College of Education at Butler University, teaches applied educational neuroscience/brain and trauma to candidates in the certification program. Desautels also creates webinars demonstrating how educators and students must understand their neuroanatomy to regulate behavior and calm the brain. Her work and new book, Connections Over Compliance: Rewiring Our Perception of Discipline, can be found at her website revelationsineducation.com.

When asked how stress impacts a student’s brain, Desautels tells Endominance, “When students’ brains and bodies perceive a threat, they protect and defend through their behaviors. As a result, when they are angry or anxious, their nervous systems are not available for learning, reasoning, logic or rewards, and consequences.” She believes using preventive brain-aligned strategies can help students with self-regulation, anger management, and the ability to control their behaviors. Assisting students in regaining their calm after misbehavior does not mean there are no consequences. Instead, it ensures that the right lesson is learned. Desautels is now combining her work with the perspective of the Polyvagal Theory to promote healthier student-teacher relationships. Dr. Stephen Porges (who first presented the theory in 1994) asked Desautels to create modules for the Polyvagal Institute sharing how the approach can inform educators and students in recognizing their autonomic states. Before diving into these new strategies, let’s look at the fundamentals of the polyvagal theory.

What is the Polyvagal Theory?

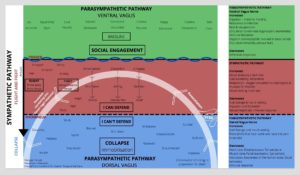

, a professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, Distinguished University Scientist at Indiana University, and the founding director of the Traumatic Stress Research Consortium in the Kinsey Institute, is best known for developing the polyvagal theory. The theory links the evolution of the mammalian autonomic nervous system (ANS) to social behavior. It highlights the importance of the physiological state in expressing behavioral problems and psychiatric disorders. Simply put, it explains the interplay between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the ANS when dealing with trauma and pain. The polyvagal theory consists of three components of the ANS and their responses, including:

- Immobilization – parasympathetic system

- Fight or flight system – sympathetic system

- Social engagement system – the ventral vagal (vagus nerve that exits the brainstem and travels through almost every body part)

Unfortunately, trauma causes major disruptions throughout all three systems and leaves most individuals in the “fight or flight” mode, resulting in feelings of agitation, aggression, and stress. So how can this theory help teachers and students? It begins with recognizing these autonomic states and learning what to do during these moments.

Classroom Management Using the Polyvagal Theory & Educational Neuroscience

Porges asked Desautels to create experientials for the Polyvagal Institute, sharing how the Polyvagal Theory can inform educators and students to recognize their autonomic states and move fluidly through those states. The polyvagal theory and educational neuroscience suggest that classrooms require “state regulation” to access and integrate the cognitive and mental tasks teachers and students need to succeed in school and navigate life experiences. State regulation is a cognitive-behavioral approach teachers can use to instruct students about self-regulation, including self-discipline, emotional control, and anger management.

To better understand how the polyvagal theory transforms into educational practice, we asked Desautels first to describe how the nervous system drives student behavior. She explains, “It drives behaviors because it holds all of the sensory information coming in from an external environment and our internal environment. So how we experience the conditions around that produces our behavior. So when we encounter a relationship, an environment, or an experience that feels threatening, unfamiliar, or unsafe, our nervous system organizes and integrates that sensory information in a way where we can’t access our prefrontal cortex (which holds our executive function – emotional regulation, problem-solving, etc.). She then adds, “So the student behaviors we see at that moment such as being defiant, shutting down, or being disruptive – those behaviors are just signals of a nervous system that is trying to express how it’s experiencing the moment.”

Image Credit: Polyvagal Institute, Revelations in Education: Created from work of Dr. Stephen Porges & Deb Dana

Desautels also explains how our nervous system affects hearing. She states, “When a student is in a survival state, their hearing becomes heightened. This happens because, from a survival standpoint, researchers found hearing muscles expanded to help humans hear predators. So when a child is in the fight, flight, or freeze state, their hearing expands – allowing them to hear everything around them. So when teachers are threatening or lecturing in the heat of the moment, the child does not hear anything they say – they’re too overwhelmed.” So how can educators help students recognize what happens during these states? With a little help from an animated figure called “ANS.”

How “ANS” is Helping Students

To help students of all ages understand their nervous system, Desautels and her team created an animated figure called “ANS,” short for Autonomic Nervous System. Educators can use a poster-size version of this figure (or other methods) to help students post how they feel every day. It helps them to track their autonomic states. She explains, “We use this technique to share with our students that it’s normal to feel agitated, worried, or shut down, or even feeling unsafe because we move through those phases of our nervous system all day long. What’s important for students to understand is that we’re not talking about behaviors; we’re talking about the science underneath the behavior.”

Desautels goes on to discuss the objectives behind these classroom management techniques, “These strategies are powerful ways for students to understand that the goal is not always to be regulated. Instead, the goal is to recognize when you’re dysregulated. It also helps the student realize there is nothing wrong with them. Instead, they understand that the brain and body are always experiencing things around them – that it’s ok, it’s human. This empowers students; it gives them a sense of control.”

The Benefits of Co-Regulation

Understanding these states helps prepare the student’s nervous system for the challenges and lived experiences during their day. When students intentionally acknowledge their ANS, they build their bodies’ capacity for safety and connection. However, the benefits of these classroom management techniques do not end with the student. Educators also use these state-regulation strategies. Before helping a student who has made a poor choice of behavior regain their composure, teachers need to be aware of their sensations and feelings before disciplining a student.

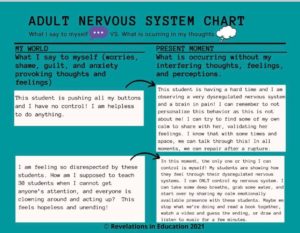

Desautels explains, “Co-regulation is so important because when we, the adults, are making sure that our nervous system is calm, we can effectively check in with our students. Then we can deliver a conversation or consequences that everybody is collaborating within. We can hear each other, and we can respond rather than react.” The below chart gives a few examples of how teachers can practice recognizing their “Adult Nervous System” during tense situations with students.

Image Credit: Revelations in Education

According to the course description, Desautels, her team, and Dr. Porges all hope that these polyvagal modules for educators will serve as road maps to help guide them toward growth. They hope it will help them model the complex and beautiful ways our brains and bodies are always communicating and working for us, not against us.